Viewpoint from the Nest – Travel parenting insights

Sucre and Potosi are cities not built for mainstream tourism. The surroundings can be gritty, and tourist sites are few relative to other parts of Latin America. They are, however, part of a route to take if you’re planning to acclimatize to the altitudes of Uyuni without taking altitude drugs, particularly useful if you’re travelling with young children. Flying into Santa Cruz (not La Paz) and driving up over a few days to Sucre, Potosi and finally to Uyuni worked very well for us, without the need for Acetazolamide for our daughter. Children seem to acclimatize better than adults and this exploratory route allows the time to do so.

A key attraction are the local markets, which are mesmerizing with vivid colours and a frenzy of movement; porters barrelling their way through packed narrow corridors, shoppers weaving their way often pulling little ankle-biting carts. There are great photographic opportunities of local Aymara merchants and customers, although many of them are not keen to have their pictures taken. It’s a true test of your non–verbal diplomacy, and your ability to snap surreptitiously. A local guide is recommended to explain all the different types of food here, and how they are prepared.

Another key point of interest is a trip down the mines of Potosi; these are being operated as they were hundreds of years ago, with pickaxes and dynamite. Life expectancies are very short for miners, and it’s often a career choice that runs through male members of the family. You can sample the coca leaves, which improves focus and decreases appetite when chewed. The full mine experience may be too long for younger kids, but they do find it easier than adults as they often have better low light vision, and definitely do not have to duck the low beams as much as adults do.

The museum in Potosi provides an accurate, but unsettling, understanding of how slaves (or indentured servants) were employed and how they were treated. The museum does an excellent task of explaining the history, showing the process of refining the silver ore, and how it affected the lives of the workers. The use of mercury amalgamation cut short many lives, and it’s a vivid lesson on how the pursuit of wealth often is at the expense of less valued lives.

Bolivia is the poorest country in South America, and has the largest proportion of Indigenous people in its population. It’s one of the most racially/culturally diverse countries in the world, and has seen much grief and sadness brought on by occupational and colonial forces over the centuries. There are long established differences between the races, between the old wealthy families and the poor Indigenous people, between the cities of La Paz and Santa Cruz, the economic capital. Horrifying treatment and betrayals by the Spanish has left people somewhat mistrustful, and the economy has been significantly curtailed by the absence of a coastal access. We primarily went to Bolivia to go to the Salt flats of Uyuni, but found that the culture and history to be much more emotionally provocative.

We flew into Santa Cruz, whose citizens generally frustrated that much of their taxes have been used by Evo Morales to build up La Paz, which he has done quite impressively. From there, the plan was to work our way slowly up to Uyuni over several days. We didn’t want to give Colette altitude pills (Acetazolamide) because of the side effects, and kids acclimatize better than adults. This meant driving through and staying at Sucre (2800m) and Potosi (4000m) for a few days.

The highlands were largely populated by the Aymaras, the main indigenous people of the area. They were defeated by the Incans after long conflicts, who in turn were conquered by the Spanish after a short few hundred years. They’ve kept their culture quite intact, although religiously, almost all of them are Catholic. They reside across the borders of Bolivia and Peru, underscoring how modern nations slice up traditional lands.

There have been marked improvements in Bolivia in recent years, with the economy driven by Chinese demand for zinc and their neighbouring countries demand for natural gas. Their Amayra President, Evo Morales, has been in position for 9 years and has made significant inroads in supporting the Indigenous peoples. He’s controversial, and derisively treated by the right wing, but you can see the impact he’s had on the country. He clearly is driving an agenda, one that is conspicuously in La Paz.

We visited several street markets, hunting down the more obscure ones where mainly the indigenous people frequent. The markets are huge, and overwhelming with the noise and number of people pushing past us. The produce look very healthy, and the sheer amount available was staggering. This was a wholesale market that felt like a small village market.

The number of species of potatoes were stunning. Being used to the few species that grow/store/ship well in most developed markets, the colours, flavours and shapes of the local “papas” – potatoes were remarkable. After running Pringles in the North Asian markets for years, Yi Ta realized how little he knew about potatoes. Quite humbling indeed.

The Aymara here were not amenable to having their photos taken, so Judith had to depend on her smiles and chatter to get them to open up. She was astonishingly effective, but one older lady was not so forthcoming and chased her to give her a sharp smack on her bottom as a refusal; it was far from an affectionate love tap, and had us howling in laughter. They are known to smash cameras so I think we got away with a great experience.

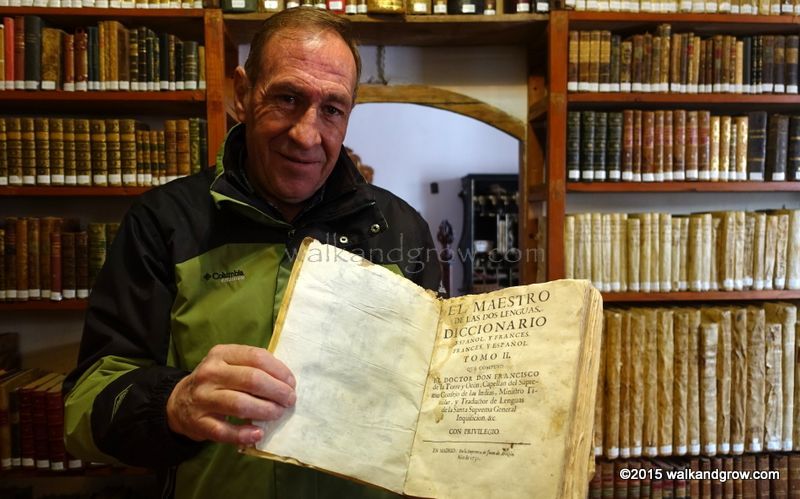

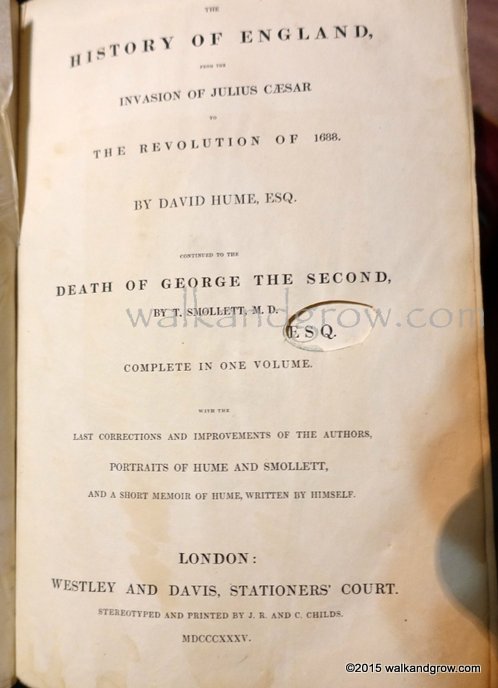

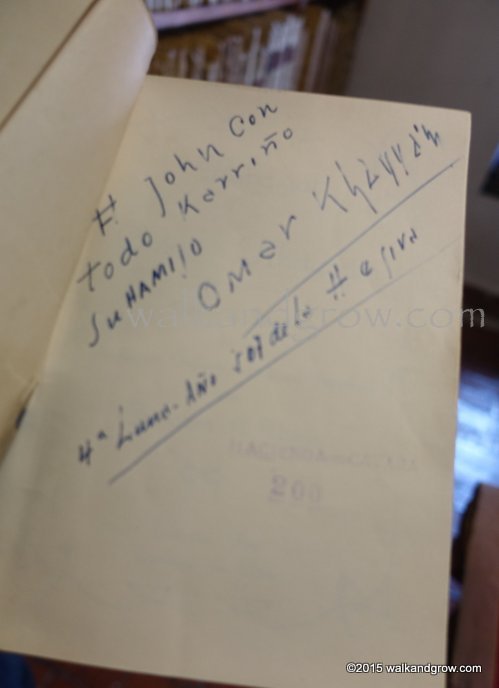

The road to Potosi had an unexpected surprise; our hotel, the Museo Cayara, had the most amazing private collection of armour, art, and artifacts. Most were discovered and passionately restored, identified, and catalogued by the owner, Arturo and his late Uncle over decades. It was a delight to encounter such dedication, and to be privy to the tales around the exhibits. Apart from the original armour of Pizarro, there was a library full of aged books and maps. There was an 1835 History of England by David Hume the philosopher, a very old copy of the Rubaiyat, and a 1731 dictionary from the time of the Spanish Inquisition:

Arturo is an extremely interesting man, and we could have easily stayed at his hotel for another day or two.

Potosi was once the world’s richest city, when it’s silver funded the Spanish empire. Life spans were short for the slaves, and near slaves, who worked the mines; the high use of mercury to amalgamate the silver also killed the workers quickly. There was so much wealth in Potosi that we could see many daily household items made of pure silver; it’s now a rather sad place, with mines still in use by the poorest of the Bolivian citizens. They now mine copper and other metals, but the return is meagre, and the silica laden air in the mines crippling lungs. We did a mine tour, and bought a few supplies for the miners, including some dynamite (which Colette is holding), pure alcohol and Coca leaves (the raw material for Cocaine). Yi Ta chewed Coca leaves for a couple of hours, but didn’t feel its appetite suppressant effects. The tough Bolivian meat did a better job with that.

The mines themselves are being used as they were centuries ago; place some dynamite to break walls and move far away. Picks, hammers and a lot of pushing a cart in and out of the mine. The miners were really friendly, and quite superstitious. Women are generally not allowed in as they would be bad luck; it won’t be surprising to find out that the women perpetuated these legends.

The miners were rightfully superstitious; the mines are hostile places and the mining vocation is one that passes from father to sons. Children as young as 12 work here, and most don’t live past 40. Accidents and ill health follow each family, and there is much to pray for. The red idol is that of Teo, the biblical Devil, but also an Uncle. Deities have a dual nature, not unlike the Yin/Yang of Asia; Dualism is a lot more philosophically sensible and is a legacy of their past, and has remained embedded despite the absolute Good and Evil offered by the Catholic Church. The implications of what was happening isn’t obvious to young children, who tend to see this as a matter of fact, but it is a visual memory that lingers deeply.

WHAT WE THOUGHT OF SUCRE AND POTOSI

These are not cities built for tourism. The surroundings can be gritty, and tourist sites are few relatively to other parts of Latin America. If you make the effort to go beyond the normal tourist runs, and have a very good guide, it can be one of the most affective journeys you can take. We were in the cities for 5 days so that Colette could acclimatize (most people stay less than that), but the time gave us the opportunity to explore more. Our guide and friend, Claudia, was terrific; a lawyer in her other life, she gave us a much greater understanding of the culture, the history and the drivers of the society we briefly encountered. This isn’t a child un-friendly location, but it isn’t one that is very light and fun either. It is a great life lesson though for all.

Hi Guys, what was more fun – chewing Coca or working in the mines! Such a shame you didn’t make it to the fashion show in time – you’re all wearing collectors items. Great to see all the things you’re doing.